Can AI Hear When Patients Are Ready for Palliative Care?

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance

In Their Own Words

Artificial intelligence – already a booming sector in health care — will need more than just smart innovation to succeed. It will need a revamp of regulation itself.

That’s because today’s FDA is set up to evaluate products like medicines and devices that do not usually change. By contrast, AI programs continually evolve based on the data guiding them. It won’t be sufficient to evaluate these systems just when they are built. They will need constant oversight, especially on the local level where people receive care, because patient characteristics and even data definitions can shift over time and by location, affecting AI’s results.

AI’s unique ability to learn from new information may also be its greatest weakness, and one that the FDA cannot solve alone. “We need to focus on the bedside,” said LDI Senior Fellow Daniel Herman. “That’s not a space the FDA oversees.”

Fortunately, Herman and LDI Senior Fellow Gary Weissman have identified a solution in plain sight. For decades, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has overseen clinical lab testing through a mix of requirements for local expertise, performance verification and monitoring, and external review. That system, called the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), could create the local accountability that AI desperately needs, Herman, Weissman and colleague Jenna Reece write in a recent commentary in npj Digital Medicine.

“Medicine is practiced locally. And for AI models, that local context is really important for a lot of them,” Herman said. “CLIA has been successful at local regulation of medical tests over decades. It’s a time-tested approach.”

AI systems are entering medicine even before robust regulations have been established. Already, the FDA has approved over 950 AI/machine-learning-enabled devices mostly for radiology, using regulations developed in the pre-AI era. AI systems are also being used to enter information into patients’ electronic health records (EHRs) and generate summaries of clinical visits.

But the tools can produce hallucinations—false or missing information.

AI also has the potential to introduce errors on a broader scale. Most of the data used to train deep learning AI systems in medicine came from California, New York or Massachusetts while other states are completely missing, a 2020 JAMA paper found. A system built on that data could worsen inequities in race and insurance status and miss the medical encounters of rural residents, to name a few concerns.

Still, many academic centers are pressing ahead to build their own AI systems in multiple areas, Weissman said, and most interpret them to be exempt from FDA oversight, which applies only to firms marketing across state lines. “This whole regulatory environment doesn’t account for how hospitals will oversee homegrown systems,” Weissman said.

The lab testing model of CLIA could bring a measure of safety without hampering innovation, the authors argue. Its oversight of labs’ work depends on the test’s complexity and the risk of patient harm. Lab tests with little chance of giving wrong results – like pregnancy tests — can be done at home or overseen by clinicians without lab training. Higher risk tests – like those screening for cancer or documenting a heart attack — trigger more extensive reviews that include verification and monitoring everywhere they are used.

Herman, a pathologist, knows CLIA well because he directs the Endocrinology Laboratory at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP).

CLIA works because there’s an accountable person – the lab director – at hospitals like HUP and also at private labs that receive specimens and test them. There’s constant verification that shows if the test is working today, along with explicit policies and documentation to track what’s occurring.

CLIA also requires private commercial labs to take some responsibility, and that should extend to firms that host clinical AI products, Herman said. Accountability is crucial because people’s health is at stake. Many of these AI tools are black boxes without total transparency on their inner workings. An individual clinician can’t be expected to understand all the ways such a tool can go wrong and catch errors, Herman said.

The authors acknowledge there are questions about how this oversight would be funded. There will likely be pushback from electronic records vendors and others who feel CLIA would be too burdensome and could stifle innovation.

Meanwhile, others proposals have emerged for AI regulation, calling for product testing to be strengthened through FDA or third-party testing labs, and using CMS’ existing rules to mandate local AI product oversight.

Herman and his colleagues think that CLIA would be a better fit. While it’s not perfect, “the oversight is so much higher than in most of medicine.”

Momentum for change seems to be growing. The Senate Finance Committee held a hearing in February 2024 on the promise and pitfalls of AI in health care. And another group, led by researchers from the University of Utah, Duke, and the University of Texas published a similar proposal to expand CLIA to AI about a week before the Penn LDI group posted.

Weissman says balancing regulations with innovation needs to be a priority. He compares AI to car technology. As a driver since age 16, he can change the oil. And when new developments come along, he and many others have decades of experience to inform on how to use them.

“With generative AI, we have 1 1/2 years’ experience,” he said, and even many experts don’t know how those AI programs work. “The power and ability of this technology far exceeds not just our regulatory framework but our experience and understanding of it.”

The commentary, “Lessons for Local Oversight of AI in Medicine From the Regulation of Clinical Laboratory Testing,” was published on December 13, 2024, in npj Digital Medicine. Authors include Daniel S. Herman, Jenna T. Reece, and Gary E. Weissman.

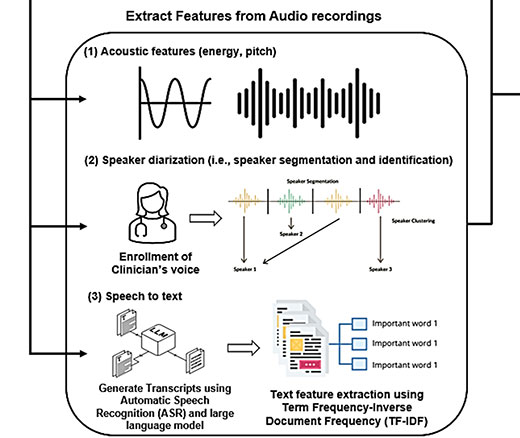

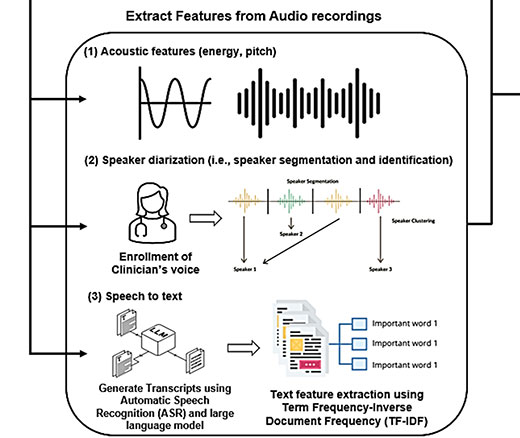

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance

A Licensure Model May Offer Safer Oversight as Clinical AI Grows More Complex, a Penn LDI Doctor Says

Study of Six Large Language Models Found Big Differences in Responses to Clinical Scenarios

Experts at Penn LDI Panel Call for Rapid Training of Students and Faculty

One of the Authors, Penn’s Kevin B. Johnson, Explains the Principles It Sets Out

More Focused and Comprehensive Large Language Model Chatbots Envisioned