Impact: LDI Fellows Shaped Public Discussion and Public Policy in 2025

Highlighting 10 Ways LDI Fellows Put Their Research Into Action

As the new year begins, we look back at a dozen of the most significant LDI news stories published in 2025. Together, they capture many of the most urgent challenges facing U.S. health care policy, including the destructive effects of the new administration’s anti-science health policies, the accelerating and disruptive rise of artificial intelligence across the health care delivery system, the dismantling of the nation’s vaccination infrastructure, the continuing harms of health care corporatization, and a growing retreat from documenting and addressing health disparities.

The Price of Obamacare Subsidies Loss: Millions Uninsured, Thousands at Greater Risk

Penn LDI/Tradeoffs Panel Discussion Eyes Impact of December Congressional Cutoff

After Fifteen Years, is Value-Based Care Succeeding?

Penn LDI Debates the Pros and Cons of Payment Reform

Black Maternity Patients More Likely to Experience Clinical Communications Failures

New Penn LDI Study Is Based on Hospital Incident Reports Rather Than Electronic Health Records

Shutting Down Federal Support for LGBTQ+ Health Care and Research

Penn Medicine Health Equity Week Panel Eyes an Extraordinary Unraveling

Penn Experts Warn New Vaccine Policy Could Undermine Public Health

Offit and Buttenheim Criticize HHS Placebo Trial Mandate as Unethical, Misleading, and a Threat to Vaccine Confidence

How Corporatization Continues to Change U.S. Health Care

Penn LDI Virtual Seminar Featured Top Experts Analyzing the Issues

In the Loop or On the Loop: The Conundrum of AI Clinical Decision Support

2025 Penn Nudges in Health Care Symposium Focuses on the Human-Machine Interface

National Academy of Medicine Issues Code of Conduct to Guide Health Care’s AI Revolution

One of the Authors, Penn’s Kevin B. Johnson, Explains the Principles It Sets Out

AI Pushes Medical Schools Into New Era, but Are They Prepared?

Experts at Penn LDI Panel Call for Rapid Training of Students and Faculty

Why Population Health Programs are Such a Challenge for Health Systems

An Analysis of Penn Medicine Healthy Heart Program Provides Insights

Using Tax and Labor Policies to Improve Population Health

A Penn LDI and Opportunity for Health Lab Virtual Seminar Explores Economic Assistance Programs

New APHA Book Warns Social Systems Are Driving Deepening Health Inequities

Penn LDI’s Antonia Villarruel and 10 Other Authors Map Social Determinants Across Multiple Racial and Ethnic Groups

Highlighting 10 Ways LDI Fellows Put Their Research Into Action

From AI-Powered Public Health Messaging to Stark Divides in Child Wellness and Medicaid Access, LDI Experts Highlight Urgent Problems and Compelling Solutions

An LDI Expert Offers Three Recommendations That Address Core Criticisms of the ACA’s Model

Administrative Hurdles, Not Just Income Rules, Shape Who Gets Food Assistance, LDI Fellows Show—Underscoring Policy’s Power to Affect Food Insecurity

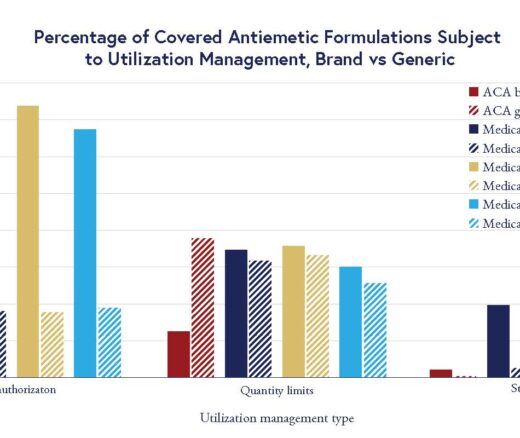

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

A Penn LDI Virtual Panel Looks Ahead at New Possibilities