Medicare’s Hidden Fix for High Drug Costs

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

In Their Own Words

The following first appeared in Health Affairs Forefront on April 4th, 2024.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) remains committed to episode-based payment models as part of its multidimensional strategy to advance accountable care. Its most recent bundled payment program, Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Advanced, has been extended through 2025. In 2023, CMS announced plans to develop a new mandatory model that builds upon lessons learned from earlier programs, which have demonstrated care transformation and reduced spending while maintaining high-quality outcomes for many episode types. Early reports from BPCI Advanced have also reported reduced spending, although bonus payments yielded net losses for Medicare. A major question for CMS is how to best coordinate bundled payments with population-based approaches, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs).

Early indications are that CMS anticipates making the new model mandatory. Yet, if this were to be the case, the future of bundled payments risks losing a major player—physician group practices (hereafter physician groups). Given that it is likely infeasible to mandate participation from physician groups, which vary in size and ability to assume financial risk, a mandatory model implies that hospitals would be the target participant.

BPCI Advanced currently allows both hospitals and physician groups to enroll as participants in the model. In fact, physician groups comprise a large share of participants in BPCI Advanced (as they did in its predecessor, BPCI). For hip and knee replacement surgery, the episode with the most consistent success overall in bundled payments, physician groups outnumber hospitals by nearly five to one. Most available evidence on bundled payments, however, ignores the performance of physician groups, instead evaluating only hospital participants.

The problem is not simply incomplete evidence on the effect of BPCI Advanced. If future bundled payment models exclude physician groups as participants, whether as a primary policy decision or secondary to other design choices such as mandatory participation, policy makers risk losing specialty physician groups as a key stakeholder in alternative payment models. This could sap momentum, or worse, compromise practice transformation and lead to suboptimal payment model results. Therefore, we argue that CMS should explicitly find a way to engage physician groups in future bundled payment models, either as direct participants or through more flexible gainsharing models, to ensure continued success in producing more cost-efficient practice patterns.

To examine the relative volume of physician group episodes, we used publicly available data from the most recent formal evaluation of BPCI Advanced to quantify episodes for physician groups as well as hospitals. We found that physician groups initiated twice as many episodes for surgical conditions as did hospitals. The converse was true for medical conditions—two-thirds were attributed to hospitals. This imbalanced distribution of medical and surgical episodes is consistent with findings from CMS’s most recent contracted evaluation of BPCI Advanced.

To examine variation in participation by clinical domain, we assigned episodes to three condition groups: predominantly medical care (sepsis, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia), predominantly surgical care (lower extremity joint replacement), and hybrid medical/surgical care (gastrointestinal hemorrhage and percutaneous coronary intervention). As exhibit 1 shows, three-quarters of episodes for lower extremity joint replacement were assigned to physician groups. The distribution of episodes for hybrid conditions fell between the extremes of medical and surgical conditions.

There are several potential reasons why surgical physician groups would be more engaged in bundled payment models than their medical colleagues, and why hospitals would shy away from surgical episodes. Surgeons may believe that they have more control over patient outcomes, with confidence in their skill of performing procedures as well as clear algorithms for patient recovery. Therefore, they may have greater willingness to accept risks for episode costs. Similarly, surgeons may exert greater control in reducing the use of postacute care, which has been the primary driver of savings in bundled payment models. For example, physicians maintain relationships with patients that predate surgeries, allowing them to set expectations for discharge home versus to a nursing facility. A programmatic reason might be that CMS preferentially assigns episodes to physician groups if physician and hospital are both participants, although our analysis shows that this occurs in fewer than 5 percent of episodes. Finally, hospitals participating in the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model cannot participate in orthopedic episodes for BPCI Advanced until the CJR expires at the end of 2024, although that applies to fewer than 15 percent of US metropolitan areas.

Greater physician group participation in surgical bundles might be dismissed as an interesting observation if it were not for another early finding from BPCI Advanced: Physician groups are better at managing cost and quality than hospitals for surgical episodes. Physician groups generate double the savings for surgical episodes as hospitals, which is particularly significant since savings in surgical bundles are already twice as large as those for medical bundles. These findings warrant independent analysis as well as examination of more recent years, given many updates to the program. However, these findings are consistent with evidence from the earlier BPCI model, which found that physician groups generated more savings for surgical than medical episodes—so these findings are unlikely to be a coincidence.

New bundled payment models will likely look different from their predecessors. CMS aims to expand accountable care to all beneficiaries and advance health equity through payment reform. For these reasons, CMS may favor mandatory models to ensure broad participation and reduce selection. Mandatory models could be feasible. The CJR and End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) models are both mandatory, and ETC includes both dialysis facilities and specialty clinicians. However, it is difficult to mandate participation among physician groups, either alone or in conjunction with hospitals, because of variation in their size, geographic location, and practice patterns. This variation may make it unfair to mandate the assumption of financial risk and doing so could accelerate consolidation trends.

However, if physician groups are not direct participants in bundled payment models, additional strategies are needed to align hospitals and specialist physicians. Gainsharing programs, through which hospitals can give financial bonuses to physicians to share gains from internal cost reductions or reductions in health spending under value-based contracts, may offer a solution. There is evidence that gainsharing has been effective at hospitals participating in bundled payments. In fact, at one hospital organization that was an early adopter of bundled payments, aligning incentives through gainsharing led not only to episode savings to Medicare but also savings on internal hospital costs from lower implant costs. Gainsharing, or other approaches to align financial incentives for physicians and hospitals, may be particularly important because more surgical specialists remain in private practice than any other type of physician. For surgical episodes in particular, effective care coordination requires communication among specialists, primary care, and postacute care. In other words, physician specialist groups may be better than, or at least necessary partners with, hospitals at managing patient recoveries, communicating next steps to primary care physicians, and troubleshooting complications in postacute settings.

Another explicit goal and unresolved challenge of bundled payment models is how best to coordinate with population-based models, specifically ACOs. Overlaps may dampen incentives for ACO participation if savings are siphoned to providers responsible for episode-based care. Overlaps also create administrative problems, such as duplicate incentive payments and complexities in calculating savings. However, the most fundamental question is how to effectively engage specialists in value-based models. To date, ACOs have been less successful at engaging specialists in practice transformation, which has major cost implications due to the high costs of specialty care. Achieving coordination between clinicians accountable for episodes (specialists) and those accountable for populations (primary care) should be an explicit objective of both model types going forward. One proposed solution is to shorten the duration of bundled payment episodes from 90 to 30 days, creating an earlier transition of care from specialists to primary care. Another solution might be to design hierarchical models that encourage coordination between accountable primary care providers and high-value episode-based specialists. Given the robust participation from and outsized success of specialty physician groups in bundled payments, policy makers should be cautious about excluding them from models, lest one key example of success in changing specialty practice patterns be discontinued.

Policy makers are actively contemplating the future of bundled payments. As they appropriately consider questions such as mandatory participation, coordination with population-based models, and practice transformation in specialty care, it is important that they keep physician groups engaged. In a future model, engagement could take the form of direct participation of physician groups but could also include alternatives such as flexible gainsharing models. Regardless, prioritizing alignment with physician group incentives and strengths is paramount.

Update: On April 10, 2024, CMS announced its new bundled payment model, TEAM (Transforming Episode Accountability Model). The TEAM model, set to launch later this year, focuses on five surgical conditions and requires mandatory participation from acute care hospitals. This design highlights the need to promote greater alignment between hospitals and physicians in pursuit of the model goals.

Read the piece in Health Affairs Forefront here.

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

A 2024 Study Showing How Even Small Copays Reduce PrEP Use Fueled Media, Legal, and Advocacy Efforts As Courts Weighed a Case Threatening No-Cost Preventive Care for Millions

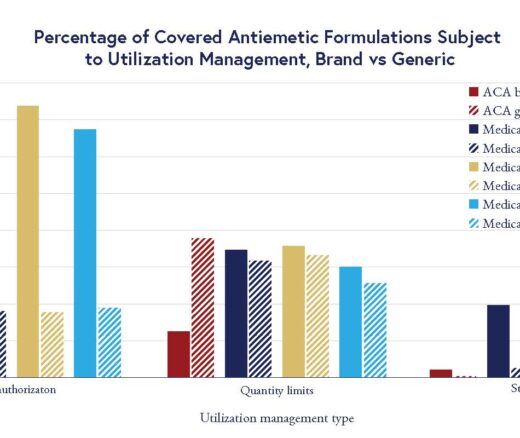

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use