How Medicaid Cuts Could Force Millions Into Nursing Homes

If Federal Support Falls, States May Slash Home- and Community-Based Services — Pushing Vulnerable Americans Into Nursing Homes They Don’t Want or Need

Improving Care for Older Adults

Blog Post | Video

Alternative payment models have been touted as a solution to reducing U.S. health care costs. Indeed, some have argued that the Affordable Care Act’s focus on alternative payment strategies—which hold providers accountable for the cost of care—is helping to flatten the famously steep curve of U.S. health care costs.

Now, a first-ever study that quantifies the effects of one payment reform on caregivers finds that a portion of the savings is accomplished by shifting the costs away from Medicare and onto caregivers, who are typically unpaid family members. The finding that these alternative payment model savings are built, in part, “on the backs of family caregivers” highlights a larger need in health policy to continue to assess the true economic cost of alternative payment models, and to adopt policy approaches that support caregivers.

The study, by LDI Executive Director Rachel M. Werner, LDI Research Director Norma B. Coe, Seiyoun Kim, and R. Tamara Konetzka, published in the American Journal of Health Economics, examined data on over 2 million Medicare beneficiaries who had knee or hip replacements, among the most common surgeries. They found that the switch to bundled payments caused a 9% to 15% increase in the need for additional help with daily tasks after paid home health services ended.

Bundled payments for common surgeries—such as joint replacement—were some of the first alternative payment models to be tested in the Medicare program. Medicare randomly selected 75 metropolitan areas to test these payment models, allowing researchers to leverage a natural randomization experiment to understand the effects of the payment policy change.

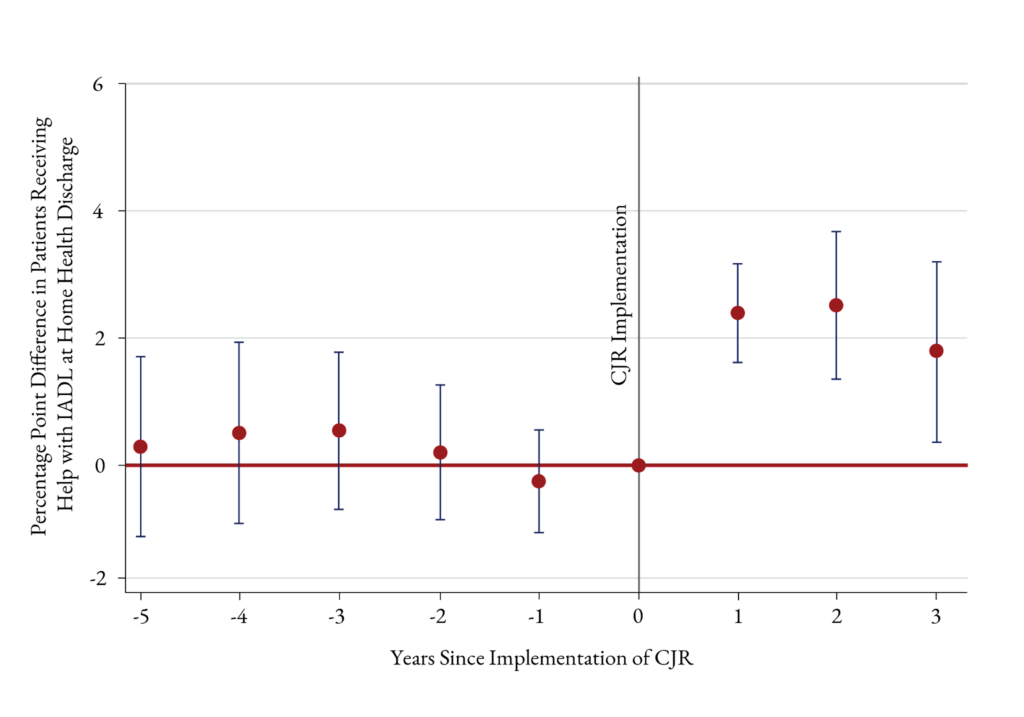

The Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) Model has been shown to successfully reduce Medicare spending by avoiding the high costs of nursing home care that often follow a joint replacement surgery. Werner and colleagues’ new work confirms prior studies’ findings that, in areas where the bundled payments were implemented, nursing home care goes down and home health use goes up. They found that the percentage of patients discharged to a nursing home declined by 2 percentage points and the percentage discharged with home health services increased by 3 percentage points. They also found that after implementation of the payment change, the number of home visits became significantly smaller. At the end of the home health episode, patients needed more help from their caregivers than they did before the bundled payment was used. The move toward care at home is often consistent with patient preferences, but it comes with a hidden cost to family members.

Werner and colleagues’ study breaks new ground by quantifying that, although paid care (i.e., nursing home stays and home health visits) declined, patients’ needs for assistance with activities of daily living did not disappear, and that care was instead provided by caregivers. Across the U.S., more than 38 million U.S. adults provide unpaid care to family members.

An increased burden of caregiving raises concern about the economic, physical, and emotional health consequences for caregivers. For example, research has shown that family caregivers are more likely to take leave from a job, take out a loan or mortgage, spend savings, hold multiple jobs, or retire early and that women are more often affected than men. “Based on the known demographics of caregivers,” the authors write, the cost of unpaid caregiving “is likely disproportionately borne by women of color.”

Prior evaluations of the CJR model estimated savings of $500-$800 per surgical episode. The investigators note that, while the dollar value of forgone wages alone for family caregivers may total less than the Medicare savings, a full accounting would require valuing the broader financial and health impacts on caregivers.

Alternative payment models have the potential to lower the costs of health care and improve quality and health equity, but understanding all the consequences of payment changes is essential to ensuring that policy changes don’t produce unintended consequences. Werner and colleagues’ quantification of the extent to which savings in the system become costs borne by family caregivers provides a blueprint for assessing current models and for the design of the next generation of payment policy.

The study, “The Effects of Post-Acute Care Payment Reform on the Need for and Receipt of Caregiving,” will be published in the American Journal of Health Economics (forthcoming). Authors include Rachel M. Werner, Norma B. Coe, Seiyoun Kim, and R. Tamara Konetzka.

If Federal Support Falls, States May Slash Home- and Community-Based Services — Pushing Vulnerable Americans Into Nursing Homes They Don’t Want or Need

Men are Stepping Up at Home, but Caregiving Still Falls On Women and People of Color LDI Fellow Says

Economist Norma Coe’s Caregiving For Relatives Informed Her Research

The Decline Since 2020 May Signal Gaps in Service and Access

Penn Event Explores the Limits of Chronological Aging and Related Issues

LDI Executive Director Discusses New Findings on Medicare Beneficiaries’ Use of Home Health