Parents Need Time, Not Deadlines, After Fetal Diagnoses

Abortion Restrictions Can Backfire, Pushing Families to End Pregnancies

Blog Post

While many studies have identified higher mental health needs among children and adolescents exposed to violence, a team of researchers from Penn LDI and colleagues in Boston and Minneapolis set out to understand the prevalence of and reasons behind unmet physical and mental health care needs in a nationally representative sample of U.S. children and youth.

They found cost-related barriers were prominent, and that less access to preventive and mental health care affects hundreds of thousands of children and adolescents exposed to violence. Their study period included the COVID-19 pandemic, which allowed them to identify some promising policy solutions.

LDI Senior Fellow Aditi Vasan and lead author Rohan Khazanchi discussed their work and its implications:

Vasan and Khazanchi: As clinicians who care for both adults (Dr. Khazanchi) and children (Dr. Khazanchi and Dr. Vasan), we’ve heard parents tell us they worry about letting their children play outside in nearby parks or participate in after-school programs because of nearby gun violence. And we have cared for youth presenting to the emergency department (ED) in mental health crises who have shared fears about past experiences with community violence or who sometimes felt re-traumatized by the sight of police officers in our hospital emergency rooms.

While each story about neighborhood violence is unique, there are themes about how it shapes mental and physical health in direct and indirect ways. The increased stress of violence exposure and resource deprivation in areas more impacted by violence has clear public health consequences.

Vasan and Khazanchi: We found that neighborhood violence exposure was associated with higher rates of delayed and forgone mental health care, less access to prescription drugs, increased rates of delayed medical care, trouble paying medical bills, and more urgent care and ED utilization. These associations were present even after adjusting for factors like family income, rurality, and insurance status. Our study helps conceptualize violence exposure as both a direct driver of health inequities and a consequence of fundamental causes like structural racism and poverty. Our findings suggest that the drivers of adverse health outcomes include cost-related barriers and decreased access to preventive care, mental health care, and medications.

Importantly, we identified some preliminary associations that suggest pandemic-era policies may have helped and may be worth sustaining in perpetuity. Even after adjusting for violence exposure and all other covariates, the 2021 survey year was significantly associated with lower odds of forgone prescriptions due to cost, trouble paying medical bills, urgent care use, ED use, and hospitalization. Decreases in cost barriers and acute care use could be explained by a combination of pandemic-related reductions in overall health care and prescription drug utilization, child poverty alleviation measures such as the temporary Child Tax Credit expansion, and coverage expansions for children such as continuous Medicaid coverage during the federal COVID-19 Public Health Emergency.

Vasan and Khazanchi: Neighborhood violence is associated with many adverse physical and mental health outcomes among children, including worsening school performance and higher rates of substance use disorder, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), asthma, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol. Our work adds to the list of myriad harms by demonstrating that neighborhood violence is also associated with more acute care utilization and greater barriers to accessing needed care for children and youth; we identified more ED and urgent care encounters, unmet medical and mental health care needs, and trouble paying medical bills or affording needed prescription drugs. It follows, then, that if we prevent or reduce childhood exposure to violence, we might reduce downstream costs to the health care system and harm to children’s health.

Vasan and Khazanchi: Caregivers in areas impacted by violence also may face trauma and poverty-related bandwidth constraints that make it more difficult for them to access needed medications and preventive health services. This is especially reflected in findings of increased trouble paying medical bills, forgone prescriptions due to cost, and delayed or forgone care due to cost among children exposed to violence. Emergency departments and urgent care centers should consider incorporating low-barrier referrals to medical-financial partnerships and to community-based groups supporting families exposed to violence. This could also help lower barriers to entry by offering multiple “doors” for families to gain access to social services and resources.

Vasan and Khazanchi: Our study makes it clear that children and youth exposed to violence have greater unmet health needs, especially mental health needs, than their peers. This deserves targeted attention. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), like neighborhood violence, are associated with consequences that start in childhood and span the life course: Children exposed to violence have higher rates of developing physical and mental health conditions like substance use disorders, anxiety, depression, PTSD, asthma, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol.

These immediate and long-term health consequences are costly. In 2020, the total cost of firearm injuries and deaths in the U.S. was $493 billion, with $78 billion attributed to youth firearm injuries. The spillover consequences are tremendous too: children and adolescents who survive firearm injury have 17 times greater health care spending (an average increase of $34,884 over the next year), and their parents experience similar increases in mental health symptoms and care utilization.

Vasan and Khazanchi: We highlight two options that have been proven in randomized or quasi-experimental studies: (1) abandoned housing remediation, which has been shown to reduce the incidence of weapons violations, gun assaults, and shootings; and (2) cash transfers to alleviate poverty, which have been shown to reduce homicide and violence-related hospitalization rates. These studies suggest that place-based investments in neighborhoods more affected by violence can help by repairing and improving the social conditions that create disparate harm.

Vasan and Khazanchi: We have an upcoming study that hones in on the adolescent mental health crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand whether adolescents exposed to ACEs faced greater mental health symptom burdens, more barriers accessing needed care, and pursued acute health care more often. While this study and our prior work on neighborhood gun violence and parental incarceration are looking at associations rather than causal inferences, we hope that they can inform future work with the aim of drawing causal links. We want this work to inform clinical practice, institutional initiatives, and policymaker interventions.

We are also looking forward to results from the IGNITE randomized controlled trial, a large study led by LDI Senior Fellows Eugenia South and Atheendar Venkataramani. The IGNITE study is focused on delivering a suite of environmental and economic interventions to individuals and families in predominantly Black neighborhoods in Philadelphia. Our hope is that the results can provide more causal evidence for how environmental and economic interventions can address the root causes of neighborhood violence and health disparities.

The study, “Health Care Access and Use Among U.S. Children Exposed to Neighborhood Violence,” was published in June 2024 in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Authors include Rohan Khazanchi, Eugenia C. South, Keven I. Cabrera, Tyler N.A. Winkelman, and Aditi Vasan.

Abortion Restrictions Can Backfire, Pushing Families to End Pregnancies

They Reduce Coverage, Not Costs, History Shows. Smarter Incentives Would Encourage the Private Sector

Research Brief: Less Than 1% of Clinical Practices Provide 80% of Outpatient Services for Dually Eligible Individuals

New Findings Highlight the Value of 12-Month Eligibility in Reducing Care Gaps and Paperwork Burdens

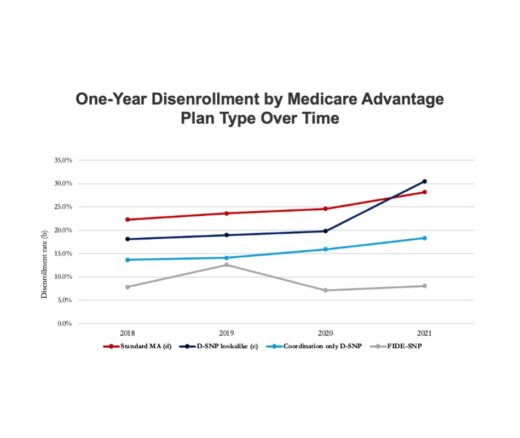

Chart of the Day: Fully Integrated D-SNPs Kept These Vulnerable Patients Enrolled, a New Study Finds

Democrats Must Go Beyond Reversing Trump-Era Cuts With a New Strategy to Streamline Coverage, Reduce Waste, and Expand Access to Medicaid