Less Postacute Care for Medicare Advantage Beneficiaries Does Not Mean Worse Health

Research Brief: Shorter Stays in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Less Home Health Didn’t Lead to Worse Outcomes, Pointing to Opportunities for Traditional Medicare

Blog Post

Last year, Congress required all states to provide one year of coverage for children determined eligible for Medicaid. The policy, known as “continuous eligibility,” is designed to ensure that children don’t have gaps in coverage—and in care—even if their families’ income changes during the year. The new federal budget reconciliation bill that Congress passed in June 2025, however, contains provisions directing states to increase, rather than decrease, the frequency of eligibility checks. While that law focuses on eligibility checks that will reduce adults’ coverage, research shows that when parents lack health insurance, children are also more likely to go uninsured. Additionally, the Trump administration recently announced that it will no longer allow states to offer enrollees multi-year continuous eligibility. As policymakers weigh the importance of coverage stability, LDI Senior Fellow Aditi Vasan has completed new research that helps quantify the impact of Medicaid continuous eligibility policies on children’s health care use.

Vasan: We believe this is a critical moment to study continuous eligibility and its impacts on children’s health and health care utilization. Twelve-month continuous Medicaid eligibility for children was previously a state policy option but became mandatory for all states in January 2024. Also, several states are now implementing multi-year continuous eligibility for children through Section 1115 waivers. The Trump administration recently signaled it will no longer approve these waivers, making research on their effectiveness especially urgent. We wanted to leverage the natural experiment created by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), where some states newly implemented continuous coverage while others already had this policy in place. This allowed us to isolate the policy’s effects from broader pandemic-related changes in children’s health care access and utilization.

Vasan: Among publicly insured children, the group most likely to benefit from this policy, we found significant reductions in coverage gaps (2.2 percentage point), unmet health care needs (1.4 percentage points), and the time families spent coordinating care (2.5 percentage points). States that newly implemented continuous eligibility under FFCRA saw a 0.7 percentage point relative reduction in children’s unmet healthcare needs across all kids. These findings collectively suggest that continuous eligibility policies may modestly reduce children’s unmet health care needs, improve continuity of coverage, and decrease administrative burdens for families.

Vasan: The increase in unmet need across all groups likely reflects pandemic-related disruptions in children’s health and health care access. Early in the pandemic, parents may have avoided seeking care due to COVID-19 exposure fears, while hospitals and clinics limited routine procedures and visits to preserve capacity. These increases may also reflect new needs arising from social isolation and stress.

However, despite pandemic-related disruptions, we found that states newly implementing continuous coverage saw more modest increases in unmet health care needs compared to states with existing policies. This suggests a potential protective effect of continuous eligibility. Without the FFCRA policy, increases in unmet need may have been even larger. The COVID-19 context may have made it harder to observe the full benefits of continuous coverage, but we think the modest protection we documented is still meaningful.

Vasan: Parent-reported data is subject to recall bias and may be less accurate than administrative data when capturing coverage changes and health care utilization. However, parent-reported coverage data is also useful because it reflects families’ perceptions of coverage. Administrative data may miss the disconnect between actual and perceived coverage and how that affects patterns of accessing care. Not all families may have been aware of FFCRA’s continuous coverage provision. Previous studies have documented a phenomenon termed the “Medicaid undercount”—a phenomenon in which beneficiaries erroneously reported losing coverage during FFCRA—limiting their ability to benefit from the policy.

Other key limitations include the pandemic context, which dampened our ability to observe changes in healthcare utilization patterns, and an insufficient sample size to examine subgroups, such as children with special health care needs or varying household income levels. Our measures also captured whether children had any preventive care and acute care visits, but not the frequency of those visits, potentially missing more subtle or nuanced changes in care access.

Vasan: The modest but meaningful benefits we observed, particularly for publicly insured children, suggest that continuous eligibility policies may improve continuity of care and reduce unmet health care needs. However, the lack of changes we observed in health care utilization indicates that providing continuous coverage alone may not be sufficient to improve access. Families may still face barriers like limited provider availability or difficulty scheduling appointments.

Families may benefit most from continuous eligibility policies when paired with additional interventions like improved network adequacy, enhanced care coordination, and robust family support for navigating health care systems. States should also invest in outreach, to ensure families understand continuous coverage policies and how they affect their children’s access to care.

Vasan: We’re pursuing both quantitative and qualitative approaches to understand the effects of 12-month and multi-year continuous eligibility policies as they are implemented. We are in the early stages of planning a study that will use Medicaid claims data from New York state to examine how its recently implemented multi-year continuous eligibility policy impacts children’s health care access and utilization. We’re also developing a companion qualitative study interviewing caregivers, health care providers, and policymakers to gather recommendations for maximizing family awareness and engagement. We hope that these studies will improve our understanding of both the impacts of continuous eligibility policies and the mechanisms through which they affect access to care for publicly insured children.

The study “Children’s Continuous Medicaid Eligibility During COVID-19 and Health Care Access, Use, and Barriers to Care” appeared in JAMA Health Forum on June 13, 2025. Authors include Erica L. Eliason, Daniel B. Nelson, Jordan Wood, Doug Strane, and Aditi Vasan.

Research Brief: Shorter Stays in Skilled Nursing Facilities and Less Home Health Didn’t Lead to Worse Outcomes, Pointing to Opportunities for Traditional Medicare

How Threatened Reproductive Rights Pushed More Pennsylvanians Toward Sterilization

Abortion Restrictions Can Backfire, Pushing Families to End Pregnancies

They Reduce Coverage, Not Costs, History Shows. Smarter Incentives Would Encourage the Private Sector

Research Brief: Less Than 1% of Clinical Practices Provide 80% of Outpatient Services for Dually Eligible Individuals

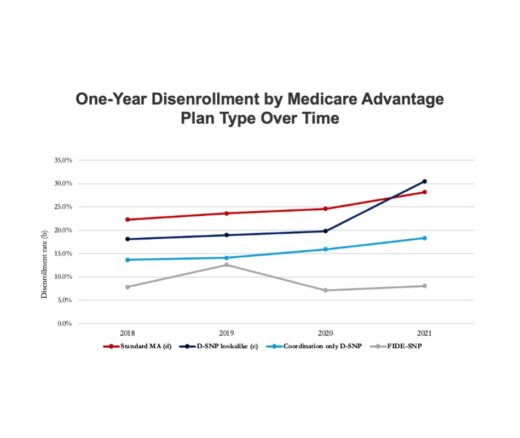

Chart of the Day: Fully Integrated D-SNPs Kept These Vulnerable Patients Enrolled, a New Study Finds