AI Breakthrough May Transform Public Health Campaigns

This Social Media Tool to Fight HIV Could Be Scaled up to Help Local Health Officials, LDI Experts Say

Blog Post

While caring for many of the sickest infants in the hospital, LDI Senior Fellow Heather Burris noticed a troubling trend: New parents with serious conditions like c-section infections and depression were avoiding the care they needed after giving birth to be with their children in the neonatal intensive care unit.

This was not unusual. She and her colleagues discovered that 41% of parents of preterm infants in a Philadelphia NICU, born between 2010 and 2019, did not receive postpartum care.

Other research showed that parents of hospitalized infants in NICUs suffer higher rates of chronic disease and pregnancy complications than parents of well newborns. Burris and colleagues sensed an opportunity to transform postpartum care for these high-risk patients: Meet them where they are with trusted professionals.

The team developed a care model to provide parents in the NICU with doula support and postpartum care from a nurse midwife. The researchers conducted a small randomized controlled trial of their model, called Postpartum Care in the NICU (PeliCaN). They found that among the 37 participants, the 20 parents enrolled in PeliCan got care a median of 20 days earlier, and they received more consistent blood pressure measurement compared to the 17 parents in the control arm of the study.

We recently asked Burris about this novel research and what might be next for the PeliCan model of care.

Burris: In my job, I encounter parents choosing to stay with their babies in the NICU instead of seeking their own health care. Yet, if a NICU parent needs urgent care, they must leave their baby’s bedside and go to the closest emergency room, requiring separation from their baby to get care. It seemed like we could do a better job at supporting mothers in getting care for themselves, for their own wellbeing, as well as to be as strong as possible for their families, especially their NICU baby.

Burris: Our PeliCaN model deploys doulas within five to seven days postpartum, typically after most mothers have been discharged from their inpatient stay. Doulas come to the NICU to meet parents where they are. Doulas interact with mothers at least once in person, and follow up via phone, text, and video chat. They help mothers overcome barriers to postpartum care.

The doulas check blood pressure, screen for depression, and practice within their scope of emotional, informational, and physical support for postpartum women. During the study, mothers could choose to see their own provider or the midwife. All intervention participants chose to see the study midwife, sometimes as their only postpartum care provider, sometimes in addition to their own provider. Since many women prefer to be in the NICU with their babies, it is critical to meet them where they are to ensure support and care.

Burris: We defined comprehensive care as screening and caring for hypertension, depression, and contraception. While we found that all but one control participant received postpartum care (albeit 20 days later than intervention participants), the bigger difference was the comprehensiveness of that care: 30% of controls were missing a core component of postpartum care, most often blood pressure measurements in the setting of telehealth visits.

Burris: There are opportunities to close this gap. I often say, ‘You can get your blood pressure checked at CVS, you should be able to get it checked in the NICU.’ However, several of our control participants never had their blood pressure checked after they left the hospital after giving birth, even though they had telehealth visits. While many of our intervention participants also had telehealth visits, they never missed blood pressure checks because the doulas ensured that they measured it for each telehealth visit.

Burris: I am thrilled at how welcoming the NICU staff were to our study doulas, seeing them as additional help, instead of an inconvenience. I believe that the shared lived experiences of our doulas with NICU mothers helped to build trust early. I was surprised that all intervention participants chose to see the study midwife; I had anticipated more mothers would want to see their own obstetric provider.

It was notable how sick NICU mothers are. We found severe hypertension even in mothers who hadn’t had hypertension before. Other mothers shared suicidal ideation requiring immediate intervention. I truly believe that doulas can be lifesaving.

Burris: Scaling PeliCaN and making it sustainable requires demonstrating its broad effectiveness across many NICUs and eventually making the business case for its value are our next steps. We are writing implementation science grants, talking to payers and policymakers, but true integration into routine NICU care will take time. In the meantime, I will be pleased if neonatologists, NICU nurses, NICU social workers, and all people working in NICUs encourage and facilitate receipt of postpartum care using our imperfect but available health care system.

Funding for this project was provided by an Optum-LDI 2022 Pilot grant.

The study, “Postpartum Care in the Neonatal intensive Care Unit (PeliCaN) – a Randomized Controlled Trial” was published May 5th, 2025 in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Maternal-Fetal Medicine by Heather H. Burris, Niesha Darden, Maggie Power, Laura Walker, Rachel Ledyard, Joseph Reiter, Jennifer Lewey, Kimberly K. Trout, Marie Tan, Emily F. Gregory, Sara B. DeMauro, Scott A. Lorch, Lori Christ, Sara C. Handley, Diana Montoya-Williams, and Celeste Durnwald.

This Social Media Tool to Fight HIV Could Be Scaled up to Help Local Health Officials, LDI Experts Say

New Findings Highlight the Value of 12-Month Eligibility in Reducing Care Gaps and Paperwork Burdens

The Prison System Often Fails to Meet Even Basic Standards for Pre- and Post-Operative Health, Experts Say

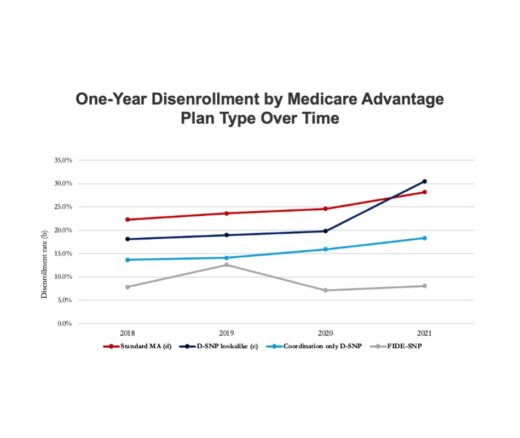

Chart of the Day: Fully Integrated D-SNPs Kept These Vulnerable Patients Enrolled, a New Study Finds

Photo & Text Story of an Urban Health Lab Initiative to Improve Health and Community Stability

Mandated Nurse-to-Patient Ratios Have Cut Deaths, Eased Burnout, and Saved Millions. Policymakers Must Act Now to Protect Patients