Medicare’s Hidden Fix for High Drug Costs

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Blog Post

What should doctors think about when recommending a medical procedure: insurance reimbursements or patient health? In a fee-for-service health care organization, reimbursement might be a consideration. In contrast, a value-based payment (VBP) system prioritizes cost management, high-quality care, and healthy patients.

The fee-for-service payment model reimburses physicians and health care systems per visit, test, and treatment. This model increases costs because it encourages excess care. It can be harmful to patients if unneeded medications have side effects or unnecessary invasive procedures have complications.

To redirect the focus to patients, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has worked for a decade to move U.S. health care to a VBP system through initiatives such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program. Practitioners and hospitals in this program form Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) that are financially rewarded when they meet quality and cost-saving benchmarks, such as for cancer screening, diabetes control, and patient satisfaction. In 2022, the program saved Medicare $1.8 billion and improved patient care quality metrics.

CMS wants all traditional Medicare beneficiaries under value-based care by 2030, but progress has been slow. A Viewpoint commentary for JAMA Internal Medicine by LDI Senior Fellows Amol Navathe and Ezekiel Emanuel, with Daniel Shenfeld from the Perelman School of Medicine, lists critical challenges—with solutions—to achieving VBP goals.

Health care organizations must be able to lower costs without reducing revenue. ACOs with a large number of primary care physicians do well in the Shared Savings Program, achieving high Medicare savings and physician bonuses. One of their strategies is using outpatient care instead of inpatient care when it is appropriate. However, these cost reductions can come at the expense of revenue for short-term acute care hospitals and skilled nursing facilities. These types of organizations might have difficulty lowering costs without cutting into revenue because of fixed expenses such as equipment, beds, and space.

In the Viewpoint commentary and two Health Affairs articles on VBP design and implementation, Shenfeld, Navathe, and Emanuel say CMS must advance ways for health care organizations to save costs without cannibalizing their income. A model with demonstrated success is the CMS Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement program that reduces patient stays at post-operation facilities after hip and knee replacements without affecting patient outcomes. A key feature of the program is bundling payments for all care for a procedure rather than reimbursing for each service, encouraging hospitals to direct patients to only necessary services. Patients who do not use post-discharge facilities because they do not need that level of care save Medicare money without affecting a hospital’s bottom line.

CMS should revise risk adjustment to eliminate “ghost savings.” VBP reimbursements are risk adjusted, with higher payments for patients who are predicted to need more care based on diagnostic codes in their records. For patients, risk adjustment levels the playing field so practices do not turn people away who need expensive care because of poor overall health.

Risk adjustment encourages practitioners to code intensively, to capture every condition that contributes to risk scores, to maximize income. A result is that Medicare patients appear sicker under VBP than fee-for-service, creating opportunities for “ghost savings” that are achieved through coding and are only on paper. Shenfeld, Navathe, and Ezekiel argue that CMS should require VBP participants to generate real monetary savings. New risk-adjustment methods could shift financial incentives away from documentation and toward improving patient outcomes.

CMS should support the VBP transition with technical help. Under fee-for-service, health care organizations determine their revenue by counting patient visits and treatments. Under VBP, organizations are reimbursed in part by meeting quality and cost benchmarks. This makes financial forecasting harder since organizations must estimate income based on events that do not happen because they are eliminating unnecessary care and costs.

Health care institutions need help making this transition. CMS must provide them with forecasting tools and software to predict and track finances under VBP. These predictive tools require up-to-date, standardized, and reliable data—and expert assistance—to interpret and apply the results. Currently, these resources are expensive so CMS must make them affordable or free.

According to Navathe, VBP shows promise: The Shared Savings Program and joint replacement programs demonstrate that VBP can work for patients, physicians, and taxpayers. However, only about one-third of traditional Medicare beneficiaries are currently in ACOs. Nonetheless, Navathe is confident that if we can solve the challenges discovered in the last decade, we can create the necessary stepping stones for future VBP success.

The article, “The Promise and Challenge of Value-Based Payment,” was published on May 20, 2024, in JAMA Internal Medicine. Authors include Daniel K. Shenfeld, Amol S. Navathe, and Ezekiel J. Emanuel.

Ongoing work by Navathe and colleagues including Adjunct Senior Fellow Joshua Liao includes studying the effect of value-based payment on health disparities, including in surgical care.

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

Pandemic-Era Medicare Flexibilities Have Proven Effective, Popular, and Safe

A 2024 Study Showing How Even Small Copays Reduce PrEP Use Fueled Media, Legal, and Advocacy Efforts As Courts Weighed a Case Threatening No-Cost Preventive Care for Millions

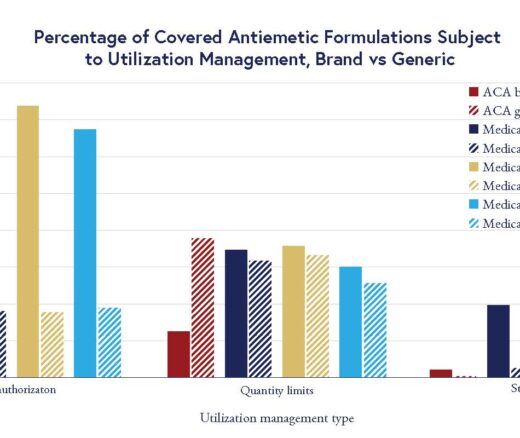

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior