Only One in Four High-Risk Rural Births Get Appropriate Hospital Care

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

Health Equity | Population Health

Blog Post

In the trauma bay and in the data on firearm injury, LDI Senior Fellow Elinore Kaufman searches for solutions to firearm violence.

As rates of firearm injury deaths in the U.S. continue to outpace other countries’, Kaufman’s research is aimed at helping policymakers understand how their policy choices can help address this epidemic. Kaufman is the Medical Director of the Penn Trauma Violence Recovery Program (PTVRP), a hospital-based violence intervention program that provides direct services to survivors of violent injury treated at Penn.

Over the past several years, she and coauthors have examined firearm injury from many angles, focusing on the role of social media and whether guaranteed income could make a difference in the recovery of victims. She has also helped create a team to support the psychological and physical well-being of shooting victims.

Kaufman discussed her research further in a series of questions below.

Kaufman: Our effort is one of the newest hospital-based violence intervention programs around the country. Some of the most established leaders are right here in Philadelphia–like the Violence Intervention Program (VIP) at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and Healing Hurt People at Drexel University. These programs have grown out of a humble recognition of the limits of clinical medicine and the desire to see our patients thrive.

As a trauma surgeon, I pride myself on fixing problems, and at Penn, we provide state-of-the-art acute care to our injured patients; including 80 people actively enrolled in our recovery program. But violent injury is a structural disease. Our patients come in with experiences of poverty, exposure to racism (including in health care settings), limited education and employment opportunities, and more. The experience of injury can compound pre-existing trauma.

Our violence recovery specialists share some background and experiences with patients and connect with them on a level that clinicians rarely can. They provide a receptive ear and service connections that can extend for months after a hospitalization.

I do this work for my patients, but it’s absolutely also for myself. When I see a patient’s high school graduation pictures or jet ski video, or hear that they are getting the psychotherapy they need, I feel like it’s all coming together.

And of course, what I learn from patients and the PTVRP team is always giving me new research ideas.

Kaufman: Fully incorporating the experiences and expertise of people closest to this challenge is not only practical but also just. Black communities have too often been seen as a source of data alone, and that can be a form of exploitation. Our neighbors tell us they want to learn from the research they contribute to, and they want resources for their communities.

Honestly, I am always working toward doing more on this. I’m learning a lot from a collaboration with my colleague Kit Delgado. We are working with health system line-level security staff to provide firearm safety information and devices to patients and visitors, and the engagement of the security team has been phenomenal. With my colleague Desmond Patton, I’m working on projects focused on the relationship between social media, violence, safety, and well-being in Philadelphia. This project will work with the true experts—our patients and young people—to design interventions that promote safety.

Kaufman: Our goal with this study was to try to find surprises. We know the general trends and demographic risk factors for firearm injury, but we were looking for outliers—counties where rates of firearm injury had increased or decreased more than would be expected over time. There were several outliers, and they raised intriguing questions. What happens at a local level that can promote positive change? What can one area learn from another? For example, Baltimore was a high outlier for homicide—a larger increase than expected over a 30-year period—while Washington, D.C., just up the road, was a low outlier. I can think of many similarities and differences between those two cities, and we don’t yet know which of those might make the difference. This study gives us a different map as to where to look for solutions.

Kaufman: The answer is: It’s complicated. Every state has its own ecosystem of firearm-specific policies. But the policy environment that affects firearm injury includes economic and social policy, too, and detangling which changes are the most important is really tricky.

My colleague Michelle Degli Esposti led a follow-up to the county-level analysis, looking at changes in state firearm laws in states that were high and low outliers for change in firearm homicide. Low outlier states did not pass any permissive laws (such as a repeal of the handgun ban or removal of a one-gun-per-month law) and they did add some restrictions such as expanding their laws on prohibited possessors, restrictions to firearms sales, or mandatory reporting of lost and stolen firearms. Missouri stood out as a high outlier, and that state repealed some important restrictions during this period. High outlier states also passed some restrictions, but these were more narrow laws, focusing on high-risk populations.

In the work with my colleague Dane Scantling, we looked at social policy and firearm policy together. We found that increased access to food benefits for those in poverty was associated with fewer firearm homicides, as well as laws limiting concealed carry. “Stand Your Ground” laws were associated with higher rates of firearm homicide (which we have seen in several other studies).

Kaufman: I became interested in the relationship between social media and violence because of stories patients told me. Social media is ubiquitous, and it can provide connection, healing, and community. But it also makes ephemeral interactions permanent and private interactions public, which can amplify conflict.

Prior work by Patton, and our ongoing work in Philadelphia, indicate that this is an important piece of the puzzle. We had the opportunity to analyze a unique police dataset with Prince George’s (PG) County in Maryland, and we found some interesting things. Many police agencies collect and use social media data in various ways, but to our team’s knowledge, the PG County police department is the only known police agency that records social media involvement routinely in every police report. We found that social media was rarely reported —much less than in my anecdotal experience—but rates did appear to rise over time. Most interestingly, where social media was used, threats were associated with a higher rate of injury, and that matches what we see here in Philadelphia.

Systematic data collection is so important, and I hope that more communities will follow the example of PG County, not necessarily only in police data, but in public health and programming contexts as well.

Kaufman: Firearm injury is a health problem, but it is highly stigmatized and does not get the dedicated attention it deserves. There is no comprehensive, national data source for nonfatal firearm injury; this drives me absolutely bananas for so many reasons.

First, nonfatal injuries cause real harm and suffering to individuals, families, and communities. They require care, and they come with costs. Second, the difference between a fatal and a nonfatal shooting only has to do with the type of weapon, the circumstances of a shooting, shooter skill, and intentionality. Also, I’m a trauma surgeon, so my goal is to turn an injury that might have been fatal into one that is survivable. If my colleagues and I do our jobs well, the rate of fatalities will be minimized, and that’s important, but it’s not the same as injury prevention.

If we want to develop and evaluate effective programs and policies for prevention, measuring only the most rare and severe outcome—death—will be misleading. We will miss solutions that could work, and we will overemphasize ones that are less effective.

Kaufman: I’m still obsessed with data sources, so we have a paper under review looking at racial disparities in fatal and nonfatal firearm injury, and a related project trying to characterize which hospitals around the country are taking care of firearm-injured patients—it’s not always the places we would expect, so this could help guide resources.

When I think about supporting patients who have survived violent injuries, I’m really proud of what PTVRP is doing, and I’m passionate about expanding our reach. I’m also very excited about our work through our citywide collaborative that looks at the role of income support for survivors. We are part of a pilot study now and are working with the Center for Guaranteed Income Research to expand and study income support in a randomized trial.

The study, “Analysis of Social Media Involvement in Violent Injury,” was published on October 11, 2023 in JAMA Surgery by Anna E. Garcia Whitlock, Brendan P. Gill, Joseph B. Richardson, Desmond U. Patton, Bethany Strong, Chidinma C. Nwakanma, and Elinore J. Kaufman.

A Multi-State Study Finds That Parents Often Travel 60+ Miles—With Distance, Insurance, and Race Driving Gaps in Maternal Care

Former CMMI Leader Liz Fowler Cites Rigid Federal Scoring Rules and Bureaucratic Impatience for Pilot Failures

A Major European–U.S. Hospital Study Finds That Changing How Hospitals Are Organized Reduces Burnout and Turnover While Improving Care Quality

Penn LDI Senior Fellow Dominic Sisti Cites “Alarming Levels”

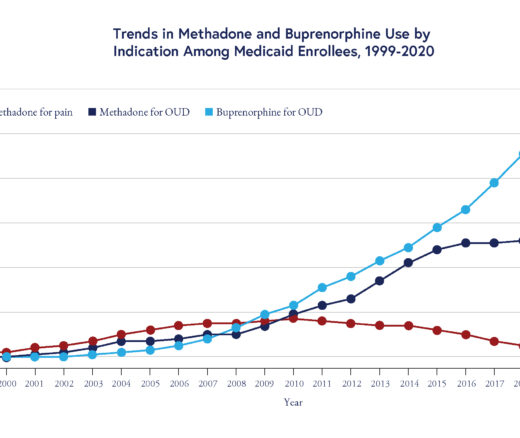

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication

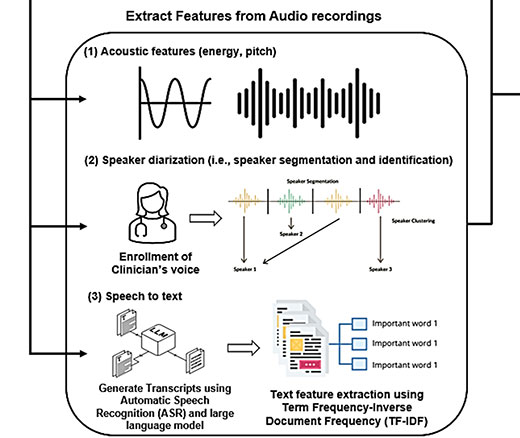

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

LDI Fellows’ Research Quantifies the Effects of High Health Care Costs for Consumers and Shines Light on Several Drivers of High U.S. Health Care Costs